Aviation Outlook Part 2: Inventories and Other Considerations for Suppliers

A recent conference recap explored demand and supply chain-related themes impacting commercial aviation, and this series continues by examining the current state of supply chain inventories with related considerations for Tier-2 through Tier-4 suppliers emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Examining inventory levels relative to deliveries

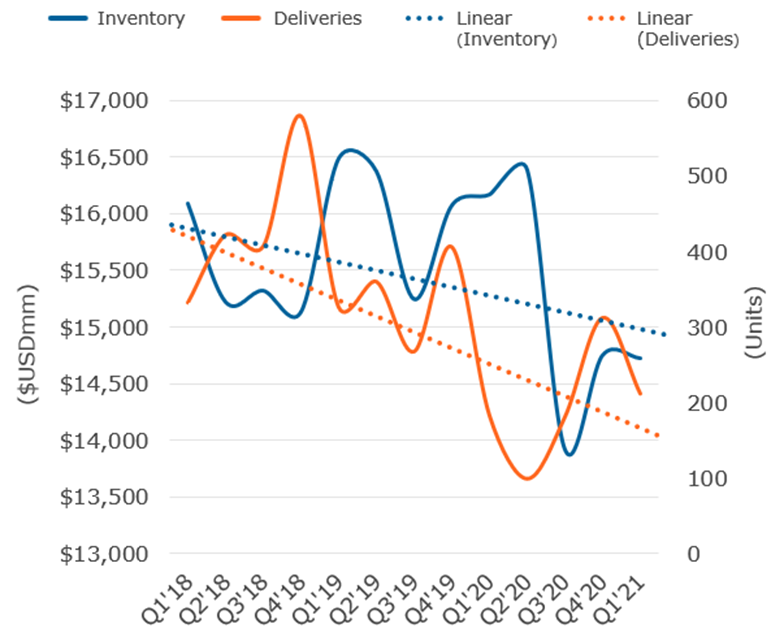

At a summary level, the commercial aviation industry’s inventory position does not look too problematic or abnormal. Peak deliveries from Airbus and Boeing took place in 2018, delivering a combined 1,860 aircraft. Since the record highs at the end of 2018, deliveries have fallen sharply, and inventory levels have followed a similar downward trend, but the details inform a holistic picture:

Figure 1: Select Tier-1 total inventory and original equipment manufacturer (OEM) deliveries

Inventories are falling, but not as quickly as production, and industry-level data can be deceiving.

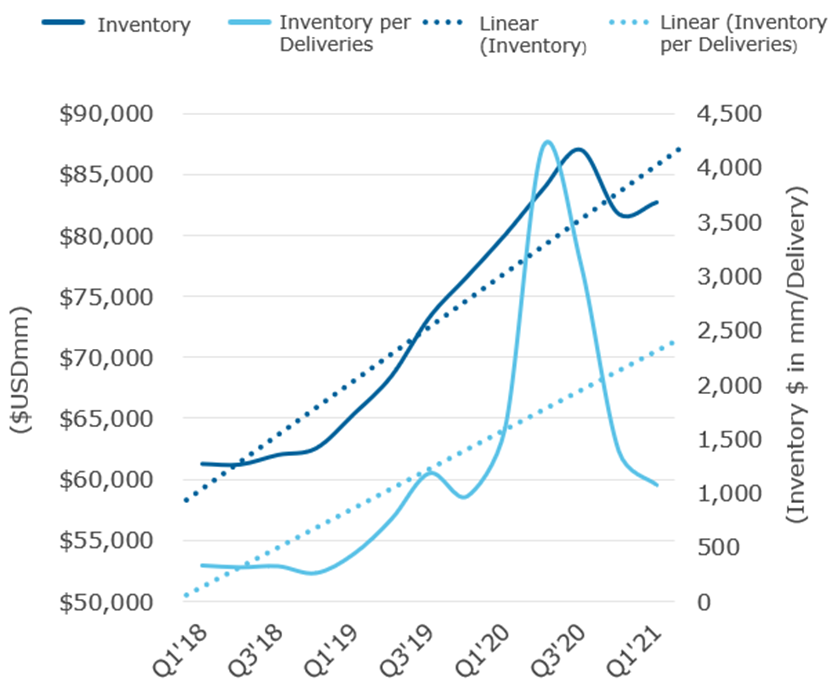

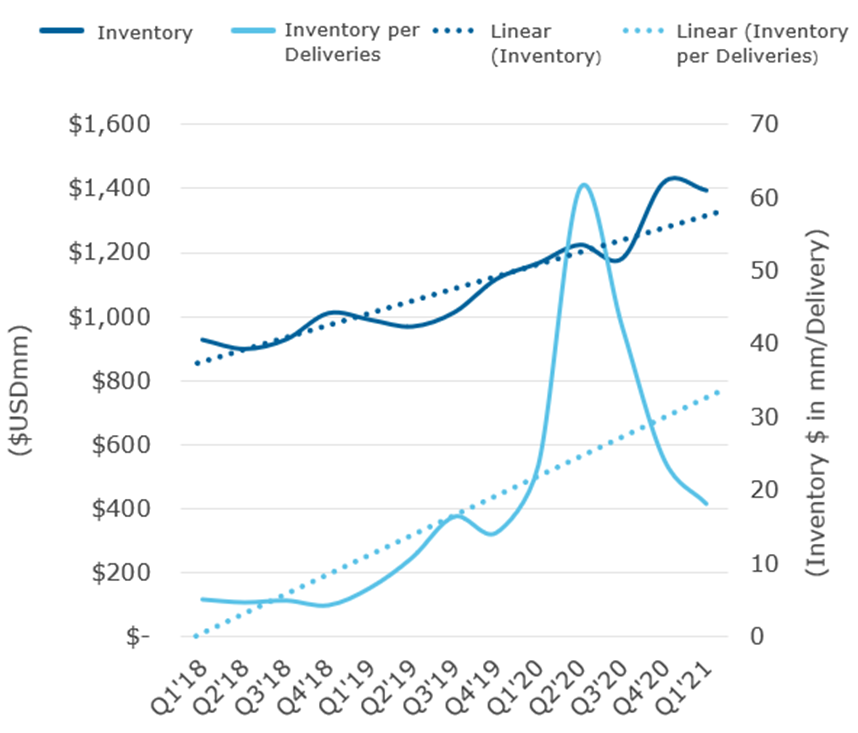

In 2019, the Boeing 737MAX was grounded due to the widely covered system issues which resulted in two fatal crashes. To maintain supply chain capabilities and cohesiveness while waiting for the FAA to re-authorize flights, Boeing chose to keep the supply chain delivering most components and assemblies at high rates well into the grounding, which took much longer than expected to be rescinded. Then, the pandemic hit in March 2020, and aircraft deliveries plummeted. The result was a dramatic increase in inventory from 2018 through the third quarter of 2020, at Boeing and Spirit AeroSystems (the manufacturer of all B737 MAX fuselages and substantial portions of the B787 Dreamliner); Boeing inventories rose from roughly $63 billion to peak around $83 billion while Spirit’s inventory levels rose from around $800 million to more than $1.4 billion. Much of Boeing’s inventory is hundreds of completed but undelivered 737 MAX and 787 Dreamliner aircraft, components, and sub-assemblies. Meanwhile, Spirit accumulated more than 100 completed fuselages and additional component inventory.

Figure 2: Boeing inventory and deliveries

Per units delivered, Boeing has roughly 300% more inventory on its balance sheet compared to 2018; inventory is a mix of finished goods and work in process. The trend is concerning, particularly when coupled with exceeding capacity in the air carrier system.

Figure 3: Spirit inventory and Boeing deliveries

Spirit inventories per Boeing delivery have increased by around three and half times from 2018 to the first quarter of 2021. The decline in the second half of 2020 was not because inventory dropped but because Boeing began delivering MAX.

The key to evaluating the current position includes looking at inventory relative to deliveries (the light blue trend lines shown in Figures 1 – 4). Compared to the peak of the market in 2018, both Boeing and Spirit have upwards of 300% more inventory per aircraft delivered. Boeing and Spirit took this action for all the right reasons, seeking to:

- keep the supply chain spooled up and able to deliver at high rates after the MAX grounding and post-pandemic, while remaining hopeful for a rapid recovery,

- keep the supply chain financially healthy,

- and protect supplier capacities from being utilized by competitors.

Unfortunately, the rebound has not been quick nor robust, and the inventory overhang will likely have direct impacts to the size and timing of demand for lower-tier suppliers.

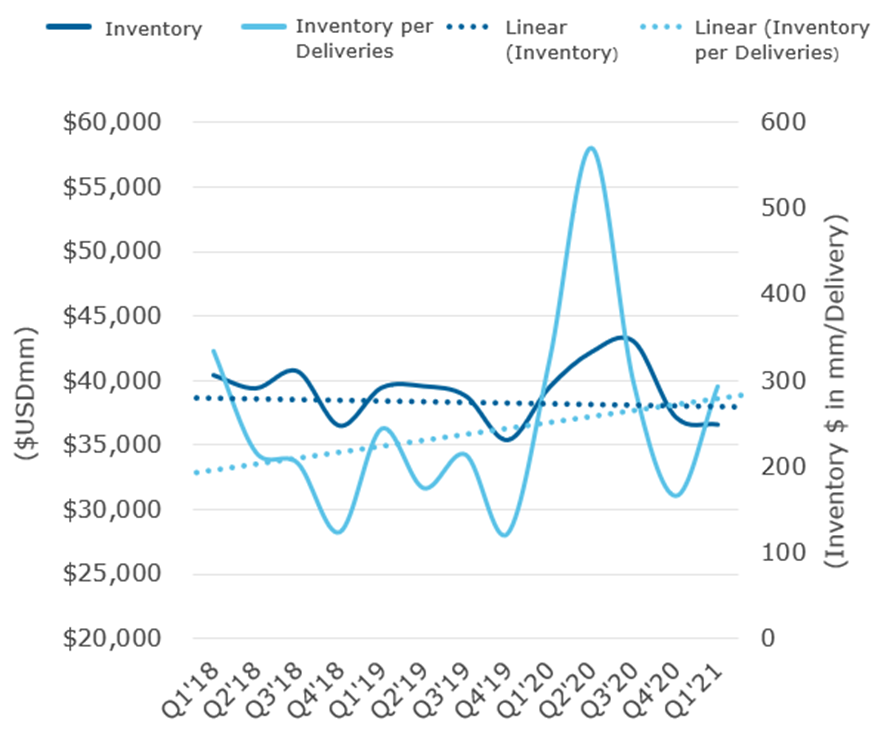

Airbus saw similar inventory and delivery trends compared to Boeing through the pandemic, but Airbus did not have to deal with the grounding of an entire aircraft family on top of the catastrophic decline in global air passenger demand, so it faced more muted impacts. Airbus inventory levels climbed from around $37 billion at the end of 2018 to roughly $43 billion in the third quarter of 2020 and then—after an uptick in deliveries in the fourth quarter of 2020—declined to more normal levels.

Figure 4: Airbus inventory per delivery

Fourth-quarter deliveries were exceptional in 2020 and helped drive down inventory per aircraft delivered; inventory per delivery increased remarkably in the first quarter of 2021. This trend should be watched closely, particularly if single-aisle aircraft line rate increases do not materialize as communicated.

Airbus faces uncertainty amid a similar trend with inventory per delivery, which is increasing to levels materially above historical norms as depicted in Figure 4. This pattern of Airbus’ is something to watch carefully, particularly if the company’s recently announced plan to move A320 production to record levels does not come to fruition. In similar fashion, many leadership teams have attempted to improve inventory levels through sales growth; sometimes these tactics work, while other times the approach exacerbates an already problematic situation.

Implications of the inventory position for the supply chain

The current state of inventory has several implications for Tier-2, Tier-3, and Tier-4 suppliers in the commercial aerospace supply chain. As stated in the first part of this series, the industry does not indicate a pressing need to produce incremental aircraft for the next several years. Estimates place a return to full utilization of the narrow-body fleet in 2023 or 2024 and the wide-body fleet sometime after 2025. As a result, line rates will likely remain below historical levels for several more years: narrow-body aircraft model rates recovering earliest, followed by wide-body models.

Considering weak demand expectations for new aircraft alongside industry inventory levels far above historically normal ranges, the Tier-2 through Tier-4 supplier level will probably face a lag in production rates for 18 months or longer. During this time, other industry players will enact adjustments as the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), Tier-1 suppliers, such as Spirit AeroSystems, and other major entities attempt to lean out balance sheets and generate much-needed free cash flow.

Regarding specific aircraft types and the perspective of OEMs, the Airbus A320 series aircraft will likely see component demand and production rates correlate in the coming quarters, while it might take as long as two years for suppliers to line up with demand for the production of B737 MAX aircraft. Wide-body aircraft from both OEMs will be challenged for an extended period because of the rapid slowdown in deliveries and demand for all types.