Value Proposition: The Core of Higher Ed Strategic Planning

A version of this op-ed article first appeared at SimpsonScarborough Insights as part one of a guest contributor series on institutional value proposition as a means of driving long-term sustainability at higher education organizations.

Never waste a good crisis

Winston Churchill famously said, “never waste a good crisis,” and the global pandemic certainly qualifies. On a scale never before seen in the United States, college and university leadership pivoted brilliantly and quickly to accommodate online education and implement emergency protocols to ensure the health and safety of students that remained on campus. As the industry turns the corner toward Fall 2021, higher education takes stock of its wins and losses: in the win column, elite universities with multi-billion dollar endowments are enjoying surging applications for the coming school year; in the losses column, many schools in the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and the Midwest are experiencing application declines. The pandemic also created funding challenges for endowments and state appropriations for many schools. For today’s crisis, the Churchillian opportunity is to take a good, hard look at each school’s value proposition with an intent to become more competitive for student applications and to make the strategic choices that drive long-term sustainability.

Which schools are at risk?

Many schools will not have the option for long-term sustainability.

Known for his ground-breaking, disruptive strategy theories, the late Harvard professor Clayton Christensen predicted in 2013 that half of all colleges and universities would close within the next 10-15 years. This was based on a confluence of factors, including an impending decline in high school graduates and the role of digital disruption throughout the industry—accelerated by the pandemic — and coupled with unanticipated financial challenges. While I do not personally believe school closings will occur in numbers as drastic as the professor’s prediction, hundreds of higher education institutions will likely close over the next seven to 10 years.

By contrast, a second category of schools has unquestioned long-term sustainability due to sufficiently stable endowments, financial stability, and brand equity.

As noted in the recently released Common Application data set, these elite schools have experienced an uptick in applications for Fall 2021. (You know who you are!)

But a third category of schools are “on the bubble” and will either survive, merge, or close.

In this category, a typical school profile has enrollments less than 10,000 students, holds a regional rather than national reputation, and likely faced pre-pandemic fiscal challenges but with sufficient liquidity to survive in the near term. Such institutions must adopt Churchill’s advice to avoid wasting a crisis. The pandemic is a crisis that gives leadership the political “cover” to diagnose current problems, develop a strategic response, and implement transformative change.

What are the “tell-tale” signals of risk?

Schools “on the bubble” are easily identified through a variety of readily available metrics, including leading, concurrent, and lagging indicators that can be used to assess risk.

Leading indicators: applications, yield rates, tuition discounting

Most schools track year-over-year applications and should be cognizant of negative volume trends across time and geographic reach. There is also an interesting development in the timing of applications that heightens uncertainty for admissions offices across the U.S. According to SimpsonScarborough’s latest research, 41% of high school seniors planning to attend a four-year college in the fall had yet to apply to a single institution as of mid-February — far beyond normal application deadlines. That presents good and bad news for many institutions. If applications are currently lagging, it may be partially due to these macro conditions, and there is a strong likelihood of classes closing late. However, indicators suggest these student populations may be more volatile and need additional encouragement (read “marketing”) to take action.

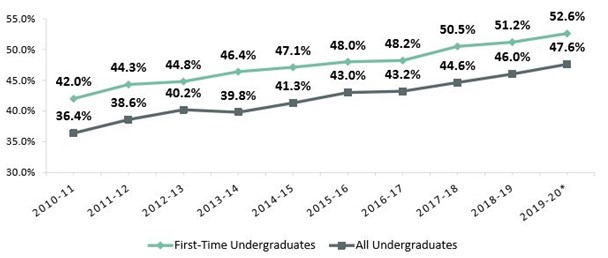

Yield rates on a negative trajectory over time can also be an indicator that the school’s value proposition has waned or has been outright lost in the eyes of the market. Increased tuition discounting is a common response to declining yield. This response is often the beginning of an unfortunate cycle of lower revenues, followed by pressure for more students to make up for the discounted tuition, and that is often followed by a lowered reputation that exacerbates the school’s undesirable yield. Educational leaders should ask themselves if the recent NACUBO study on tuition discounting (see Figure 1 below) in any way resembles their school’s experience in the past ten years.

FIGURE 1: AVERAGE INSTITUTIONAL TUITION DISCOUNT RATE, BY STUDENT CATEGORY

At increasing rates, many educational institutions contend with marked tuition discounting for students.

Concurrent indicators: graduation rates, melt, and retention

Acceptance “melt” over the hot summer is also a critical signal that something may be broken with a school’s value proposition. In the wake of the pandemic last year, there was certainly an understandable set of unique circumstances that could lead a student to back out of matriculating in the fall semester, with factors such as illness or loss of family income being the most obvious, and the same deterrents could continue for 2021.

If acceptance melt had been tracking above 15-20% pre-pandemic, such a school is already vulnerable. The enrollment trend over the past several years can be even more important than the absolute level of a school’s melt. Catching the trend proactively gives the school more time to remediate. Melt is a more prevalent issue now that—bending to pressure from the Department of Justice—the National Association for College Admission Counseling no longer bans colleges from recruiting students who have committed to attend elsewhere. Cutthroat recruiting will only turn up the heat on melt.

Once students are committed and on-campus for freshman year, keeping them all four years is the next big test of a school’s value proposition. If these students are staying and graduating, congratulations. If a school is losing more than 10% after freshman year and end up with a graduation rate of less than 60%, a thoughtful self-evaluation about the school’s marketing, admissions screens, curriculum, and campus life elements is absolutely warranted. And the past annual trend is just as important as the percentages. It is worth noting; student attrition was one of the top concerns (85%) expressed amongst college presidents this spring, according to a recent study from Inside Higher Ed. And all these component pieces, wrap around the fundamental value proposition of a school.

Lagging indicators: cash flow, covenant violations, market rankings, and accreditation

In a consulting engagement, my team advised a private, faith-based university that had been experiencing many problems: high rates of melt, retention, and tuition discounting, along with low graduation rates. The school lagged behind its benchmark competitors in all these categories, suggesting that the school had lost its footing on its true identity and core message. The problems, which had been growing for several years, caused the school to be overdependent on philanthropic support as tuition and its ancillary revenue became unstable. Diminished cash flow resulted in a bond covenant violation which triggered several conversations with the school’s bondholders. To guide this school toward positive change and long-term sustainability, all recommendations centered on refocusing and affirming the value proposition to answer the question: why do students come to this school?

Scenarios like the example outlined above show that failure to shape strategy around a school’s core brand and purpose can result in a cascade of troubles that can minimize, if not outright eliminate, a school’s options for long-term sustainability. Assessing a school’s brand equity as part of its value proposition is a critical step towards developing a comprehensive, strategic response to these leading, concurrent, and lagging risks. Higher education brand consultancy SimpsonScarborough has spent years developing brand equity scorecards for clients to help inform their brand strategies and marketing initiatives because they believe—and I agree—it is one of the single most crucial metrics that c-suite and marketing leaders, school presidents, and boards of trustees should regularly review.

The advent of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 has provided a cushion for many universities and colleges this year as they combat the impact of the pandemic. This is temporary, one-time relief from the crisis and gives a school time to assess and remediate these risks. Don’t waste the crisis.