Addressing the Tax Impacts of Cancellation of Debt Income When Restructuring

When restructuring debt as part of a reorganization, some methods offer more tax advantages than others and can be used to reduce unwanted or unexpected cash tax obligations arising from these strategic business decisions.

Amid market uncertainties, the Office of the CFO faces heightened pressure to ensure financial caution while shaping a sound path forward for the business. This balancing act is even more tenuous when the need for debt restructuring arises — often during the broader reorganization of a company due to either changing operating or financial conditions. For businesses experiencing financial stress, restructuring debt and debt workout planning may be integral to ensuring future success.

As large amounts of outstanding debt near maturity, businesses may face difficulties in satisfying or refinancing their current obligations when these become due. In response, plans for a reorganization or debt workout typically emerge to help manage the financial pressure of meeting these obligations—and CFOs may be faced with a new, unexpected tax exposure and miss an opportunity to minimize it. Without appropriate tax planning, debt restructuring may result in unnecessary cash tax costs for debtor companies, creditors, and investors.

Accordingly, it is important to examine the US federal tax implications of certain debt restructurings that can result in the cancellation of debt income (CODI) and understand opportunities for exclusion of this income during bankruptcy and insolvency. The best strategies will vary depending on the company’s tax classification and the facts and circumstances surrounding its debt modifications.

CODI and its tax treatment

Cancellation of debt income (CODI) can arise when a lender has forgiven or discharged a company’s debt, relieving the company of its obligation to pay.1 In this case, it is necessary to determine the amount of potential cash tax exposure that could arise from a CODI event. Generally, for US federal income tax purposes, CODI is realized in an amount equal to the excess of the debt forgiven when compared to the fair market value of a property or any new debt exchanged. When debt is canceled, the amount of debt forgiven is treated as taxable ordinary income to the debtor. Exceptions to recognizing CODI are available for debtors meeting certain criteria, such as insolvency or bankruptcy.

Tax considerations surrounding reorganization typically do not end with federal tax analysis. CFOs should be aware that states may vary in their treatment of CODI, and a separate analysis by jurisdiction is required to understand each state’s conformity to the federal rules and potential state and local tax exposures.

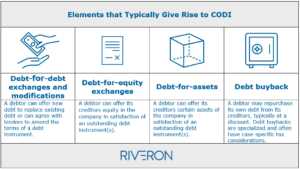

Many forms of reorganization transactions can give rise to CODI. Some of the most common examples include debt-for-debt exchanges and significant modifications of debt; debt-for-equity exchanges; debt-for-assets, and debt buyback transactions.

Debt-for-debt exchanges and modifications

A debt-for-debt exchange occurs when the creditor and debtor agree to replace existing debt with a new debt issuance, usually including a revised set of terms (such as extended maturity date, different interest rate, etc.) and covenants. As mentioned above, CODI may arise in a debt-for-debt exchange and will generally equal the adjusted issue price of the old debt minus the issue price of the new debt. 2 The adjusted issue price of any debt generally is the original issue price (i.e., the principal amount) increased by any unpaid interest and decreased by any payments of principal made. The issue price of the new debt is generally equal to the stated principal amount. For example, if a company satisfied $2 million of old debt by issuing $1.9 million of new debt, the company would realize a CODI of $100,000.

Instead of replacing existing debt with new debt, creditors, and debtors can agree to change the terms of the loans, which may result in a taxable event if the change is a significant modification of the instrument.

The determination of whether a significant debt modification has occurred is based on Treasury Regulation 1.1001-3. Some of the factors reviewed under this construct include changes in the:

- Yield

- Timing of payments

- Nature of the instruments

- Obligor or security

- Accounting or financial covenants

Additionally, modifications to an instrument that does not fall under any of the bright-line rules can still lead to a significant modification if they are economically significant when taken as a whole.3 This test will vary depending on whether the debt is recourse or nonrecourse, as well as other facts and circumstances.

Debt-for-equity exchanges

Rather than issuing new debt or modifying existing debt, some debtors may decide to grant creditor equity in exchange for satisfaction of debt. Doing this may allow the debtor to improve its debt-to-equity ratio, which may improve current cash flow and provide for additional debt capacity in the future.

In a debt-for-equity exchange, CODI for US federal income tax purposes is equal to the excess of the outstanding balance of debt over the fair market value of the equity interest granted to the creditor in satisfaction of the debt. Valuing the equity interest granted will be an important step in the process and may require significant negotiation between the parties. If the creditor (or group of creditors) receives 50% or more of the company’s total outstanding equity by value, the debtor may have an ownership change for tax purposes that would limit the use of net operating losses (NOLs) and R&D credits going forward.

A creditor may be able to defer current income tax obligations on a debt-for-equity exchange if the transaction meets the requirements of a tax-free recapitalization. While these requirements are beyond the scope of this article, one important point is determining whether the debt meets the code’s definition of security. Existing shareholders may see their ownership diluted by the issuance of new equity to the creditors; however, they will not have a taxable transaction that would cause gain or loss recognition. In circumstances where the creditor owns all the equity of the debtor prior to a debt-for-equity exchange, under IRC Section 108(e)(6), the creditor can contribute its receivable to the debtor’s capital without causing the debtor to recognize CODI.

Debt-for-asset exchanges and debt buybacks

Another alternative for the debtor to reorganize its debt is to transfer assets to the lender in exchange for debt relief. In this scenario, the debtor will recognize CODI if the debt relief obtained exceeds its tax basis in the assets transferred to the creditor.

A debtor may also realize CODI if it buys back outstanding debt from creditors at a discount. This type of transaction can occur with publicly traded debt that the debtor obtains on the open market or where the debtor directly negotiates with creditors to settle obligations for cash at less than face value. The determination of CODI in a debt buyback transaction can vary according to the facts involved in the transaction.

CODI exclusions

Once the amount of CODI is quantified, it may be reduced or eliminated if other provisions of the CODI rules apply, such as insolvency or bankruptcy exclusions. Under the insolvency provisions, CODI can be excluded from a taxpayer’s gross income to the extent of their insolvency, including the debt to be discharged. Insolvency is generally measured as the excess of liabilities over the fair market value of assets immediately before the discharge. The insolvency exclusion results in tax attributes being reduced by the amount of insolvency based on a predefined order, with NOLs being the first attribute reduced.4 This reduction would occur in the first year following the tax year in which the debt is forgiven. The debtor’s NOLs remain available to offset any taxable income in the year of discharge, which may reduce the cash tax impact of the reorganization.

To qualify for the bankruptcy exception, the discharge of debt must occur in a Title 11 case, which includes Chapter 11 reorganizations and Chapter 7 liquidations. Under the bankruptcy provisions, any amount of CODI will be excluded from the debtor’s taxable income without regard to the debtor’s insolvency. Attribute reduction as specified in IRC Section 108(b) will be required for any amount of CODI excluded from taxable income under the bankruptcy exception.

If a debtor has depreciable property as defined within IRC Section 1017(a), the debtor may make an election to first reduce basis in any depreciable property held by the debtor “at the beginning of the taxable year following the taxable year in which the discharge occurs” to the extent that the aggregate basis of the property does not exceed the aggregate liabilities of the debtor.

Shareholder and creditor considerations

Shareholders in a corporation undergoing bankruptcy or insolvency proceedings may be able to obtain a worthless stock deduction for their investment in the stock of the debtor. To qualify for this deduction, the shareholder’s investment in its shares must be completely worthless. As such, the shares must have no realistic expectation of having value presently or in the future. Similarly, lenders may be able to recognize a bad debt deduction for some or all of the amount of the debt not repaid.

Considerations for partnerships

In the event the debtor is organized as a partnership rather than a corporation for US federal income tax purposes, CODI will be generated at the partnership level. and will be included in the distributive shares of each partner holding an interest in the partnership immediately before the discharge takes place.

In the absence of a partnership agreement that provides for a different allocation methodology, a partner’s distributive share of income, gain, loss, deduction, or credit, including CODI income, must be allocated based on each partner’s interest in the partnership, determined on by taking into account all facts and circumstances.5 Once the allocation is complete, a solvency test or determination of bankruptcy status is done at the partner level to determine if the partners qualify for an exclusion of CODI. See footnotes5,6 below for other considerations.

Proactively mitigating risk

Although business and financial factors are often key drivers in a decision to restructure existing debt, companies should be mindful of the unique tax consequences that these reorganizations can have such as taxable CODI or gain recognition. Often, cash tax liabilities may be inevitable when undergoing a debt restructuring, and careful tax planning with the assistance of a trusted tax advisor is critical during the early stages of evaluating any potential debt restructuring to mitigate potentially negative tax consequences for all the parties involved.

Need help with tax advisory?

Whether your team is navigating year-end cycles, debt restructuring, or has other tax advisory needs, Riveron’s team of experts is here to help. We partner with our clients and their stakeholders to elevate performance and expand possibilities across the transaction and business lifecycle. Contact us to learn more.

Footnotes:

(1) See IRC Sec. 61(a)(12) and Kirby Lumber Co., 284 US 1 (1931).

(2) See IRC Sec. 108(e)(10).

(3) On debt-for-debt modifications: See Treas. Reg. 1.1001-3(e)(1)

(4) On CODI exclusions: IRC. Sec. 108(b) The amount excluded from gross income shall be applied to reduce the tax attributes of the taxpayer and the reductions shall be made in the following order: NOL, General Business Credit, Minimum Tax Credit, Capital Loss Carryovers, Basis Reduction, Passive Activity Loss and Credit Carryovers, and Foreign Tax Credit Carryovers.

(5) On partnerships: IRC Section 704(b) If the partners do not qualify for any CODI exclusions, under IRC Section 752(b) the partnership’s discharge of indebtedness is considered a distribution to the existing partners because of the resulting decrease in the partners’ shares of the liabilities of the partnership. As referenced within IRC Section 731, this distribution may result in a gain to the partners “to the extent that any money distributed exceeds the partner’s adjusted basis”6 in his or her interest in the partnership immediately before the distribution.

(6) On partnerships: IRC Code 731(a)(1)Under IRC Sections 705(a)(1)(A) and (B), there will also be an increase to the basis of the partner’s interest in the partnership based on the allocation of CODI. Note that this increase in basis will occur even if the partner can exclude CODI due to insolvency or bankruptcy.