How Corporate vs. Partnership Tax Structures Affect Private Equity Investments

Early in the private equity deal cycle, it’s important for management teams and CFOs to examine structuring and taxation considerations. Taxes can have a significant impact throughout the investment lifecycle of a portfolio company, and flow-through structures generally result in a lower tax expense, even if recognized at the investor level.

Private equity investors must make tax structuring decisions early in the deal lifecycle. They acquire portfolio companies and hold them for several years before selling those investments to realize the intended value. These types of deals involve many nuanced tax considerations, and it can be difficult to accurately understand the tax burden on private equity (PE) funds.

PE investments are held through complex chains of entities formed for various tax, legal, or operational reasons. The federal income taxation of these structures is dependent on entity type, tax elections, and often the tax status of the private equity investor.

Private equity funds usually operate as partnerships for federal income taxation. They accumulate capital from various investors who become private equity partners and use the funds to acquire portfolio companies as investments.

When acquiring a portfolio company, a private equity fund must choose between corporate and partnership-level federal income taxation:

- Corporate entities are subject to entity-level taxation.

- Partnerships pass through their income to be taxed at the partner level —sometimes called flow-through taxation.

Generally, PEs can choose their desired form of taxation by utilizing check-the-box elections.

The private equity tax burden: corporate versus flow-through entities

Since the tax burden depends on many factors such as profitability, cash flows, and exit value, the following insights are based on a typical successful PE investment.

Portfolio companies earn returns for the PE fund in three ways:

- Operating income, which can be retained by the portfolio company for future growth or distributed to the PE.

- Distributions of cash, which can be sourced from operating income, sales of assets, or incremental debt at the portfolio company.

- Appreciation in enterprise value, which accrues to the PE upon sale (or other form of disposal) of the portfolio company. This is also called exit value.

The makeup of a private equity fund’s overall return on an investment depends on the amount and timing of the different sources of return. Each has differing tax consequences to the PE based upon its choice of entity-level or flow-through taxation.

Example: PE fund and portfolio company tax structures

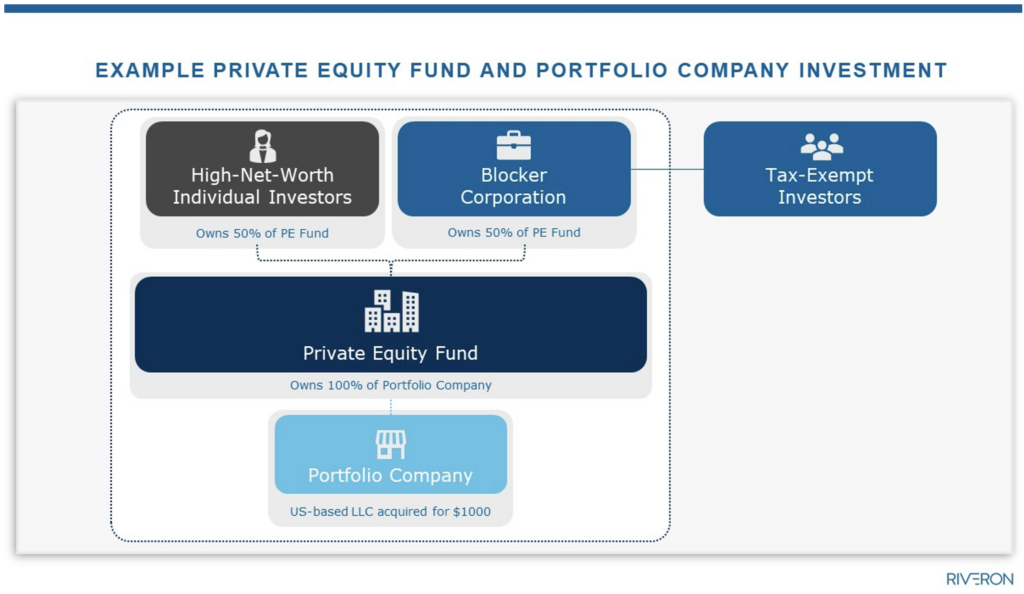

The example PE fund is a US partnership with two types of partners: (1) high-net-worth individual investors, which could include PE management or founders (these individuals pay tax at the highest marginal US tax rates); and (2) a US corporation, called a blocker corporation, which is typically formed to hold the PE interest on behalf of tax-exempt investors. Blockers are taxed at corporate tax rates and are used so tax-exempt investors do not earn unrelated-business-taxable income (UBTI). In terms of ownership, the PE is funded half by blocker and half by high-net-worth individuals.

Assume the PE fund acquires a portfolio company in an equity purchase transaction for cash consideration of $1,000. Post-acquisition, the PE fund owns 100% of the portfolio company with the intent to sell it in approximately seven years. The portfolio company is a US-based LLC, and thus eligible for a check-the-box election. The PE must choose between corporate and flow-through taxation for the portfolio company. Initially, by looking only at operating income, the PE fund might prefer a corporate structure for the portfolio company, but by looking at other factors such as distributions and exit tax, the overall tax considerations indicate a flow-through structure as a better choice.

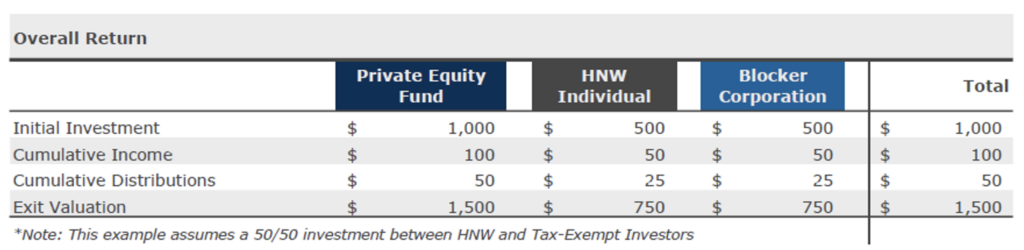

The overall return of the PE investment comes from operating income ($100), distributions ($50), and appreciation in exit value ($500). The exit value appreciation can be subdivided into retained profits ($100 – $50 = 50) and capital appreciation ($500 – 50 = 450).

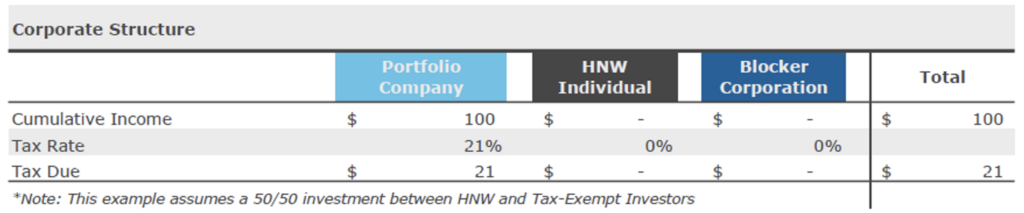

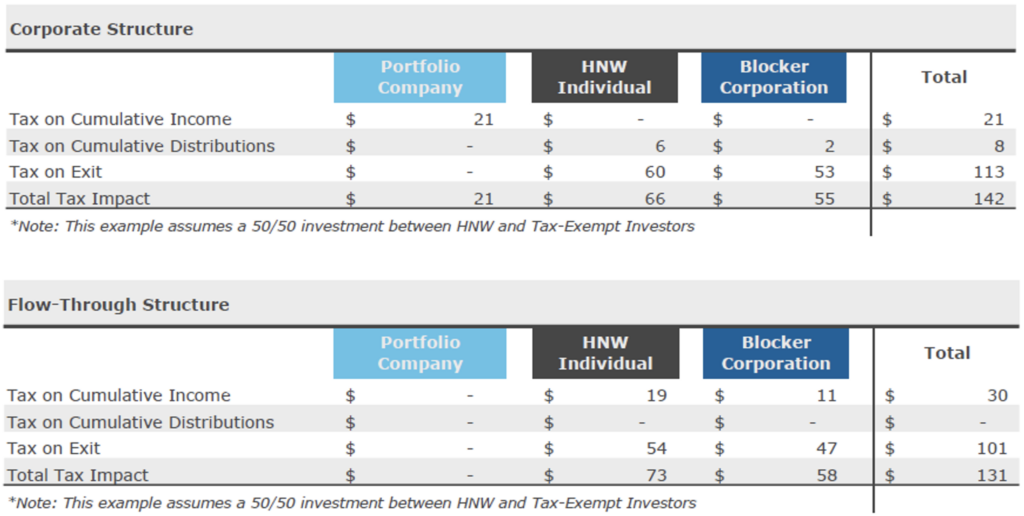

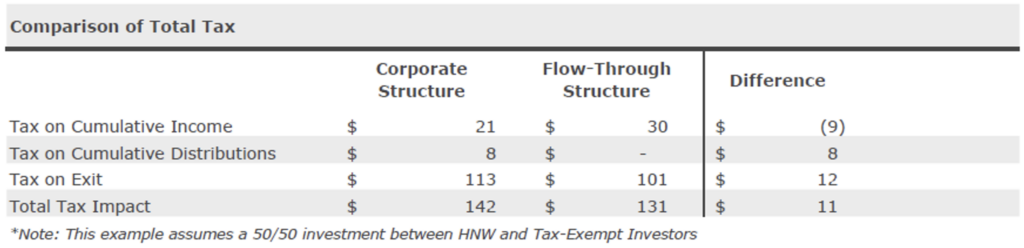

Tax on operating income may seem better with corporate structure — but it doesn’t paint a full picture

If structured as a corporation, the operating income is subject to Federal tax at 21%. This tax is assessed and paid at the portfolio company level. If structured as a flow-through entity the operating income is taxed at the partner level. For the individual partners, the income is taxed at marginal tax rates (37%). For the blocker partners, the income is taxed at the 21% corporate rate.

Since the corporate rate is less than the highest marginal individual rate, it appears the PE would be better off in a corporate structure, but (as illustrated below) this conclusion is premature and does not consider all Federal income taxes.

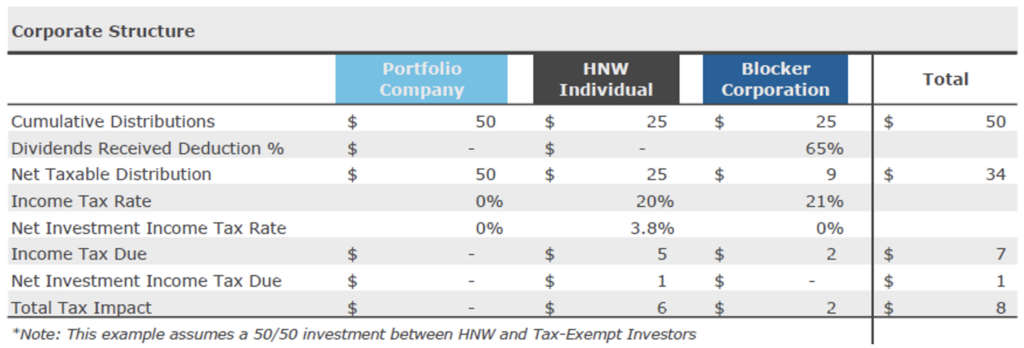

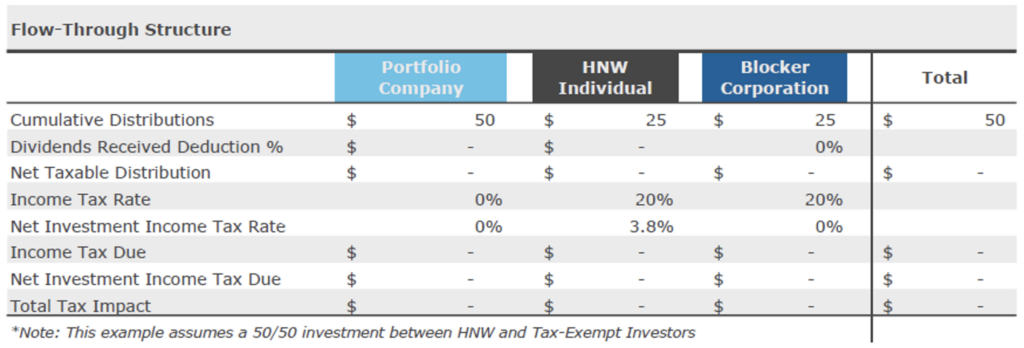

Distributions depend on shareholder factors

In a corporate structure, distributions of dividends are subject to shareholder-level tax. The tax amount depends on the tax status and ownership percentage of the shareholder.

- Corporate shareholders – Dividend income is taxed at 21% rate, but a dividends received deduction (DRD) is allowed as follows:

- A 50% DRD for shareholders that own less than 20%,

- A 65% DRD for shareholders that own 20-80%,

- 100% DRD for those owning above 80% (consolidated).

- Individual shareholders – Qualified dividend income is taxed at long-term capital gains rates (20%). In addition, dividend income is subject to the Net Investment Income tax at 3.8%.

In the following example, half of the dividend income is earned by blockers and is eligible for a 65% DRD (which depends on the number of blockers invested and assumes the minimum levels of ownership noted above). The other half of the dividend income is earned by individual shareholders and is taxed as qualified dividend income.

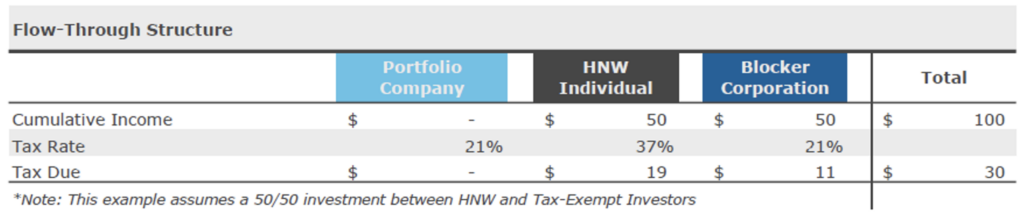

In a flow-through structure, distributions are nontaxable reductions of basis. Thus, a flow-through structure avoids the double taxation described above and is superior to the corporate alternative.

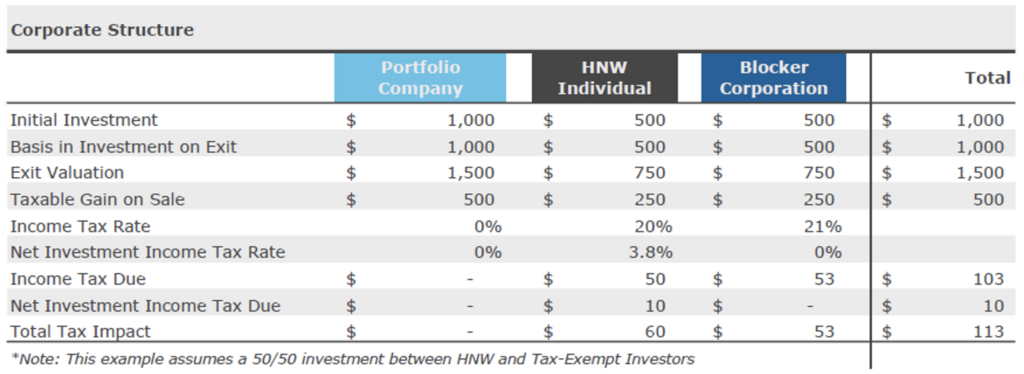

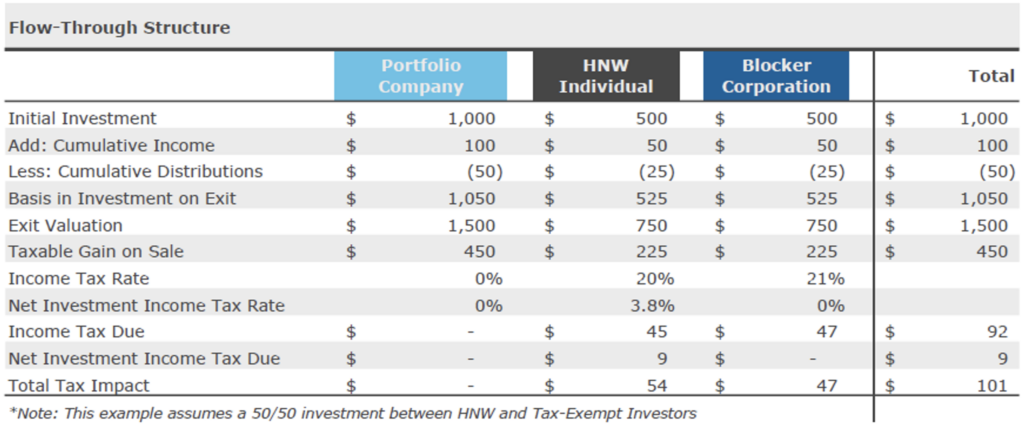

How a flow-through structure impacts the exit tax

Upon sale of the portfolio company, a gain is recognized. In both the corporate and flow-through structures capital gain is recognized by the PE and allocated to the individual and Blocker partners. Thus, the tax rates applicable to the gain are identical. However, because of the basis adjustments made to the flow-through structure the amount of the gain differs.

In flow-through structures, the basis in the PE investment is increased for income and decreased for distributions. A net increase, like the example shown below, reduces the amount of the capital gain upon exit. As a result, the overall tax burden on exit is less in the flow-through structure.

For PE funds, the overall tax burden is better using a flow-through structure

In total, the corporate tax burden exceeds the flow-through tax. This result is consistent with common industry wisdom that flow-through structures are preferable. Corporate structures are usually reserved for IPO exits, foreign entities, and acquisitions of historic corporations.

When making investments, private equity teams should model their intended sources of returns on an after-tax basis to ensure they make tax-optimal decisions.